TOYS

VIDEO AND TEXTILE

INSTALLATION SERIES

2019 — SOLO SHOW, VIDEOZAVOD, LOTSREMARK,

BASEL, SWITZERLAND

2013 — Videoprogram Variable landscape,

Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Venice, Italy

2012 — SOLO SHOW “TOYS”, TRIUMPH GALLERY,

MOSCOW

2010 — The Eighth International Photography

Month in Moscow: Photobiennale 2010,

Gallery Na Solyanke, Moscow

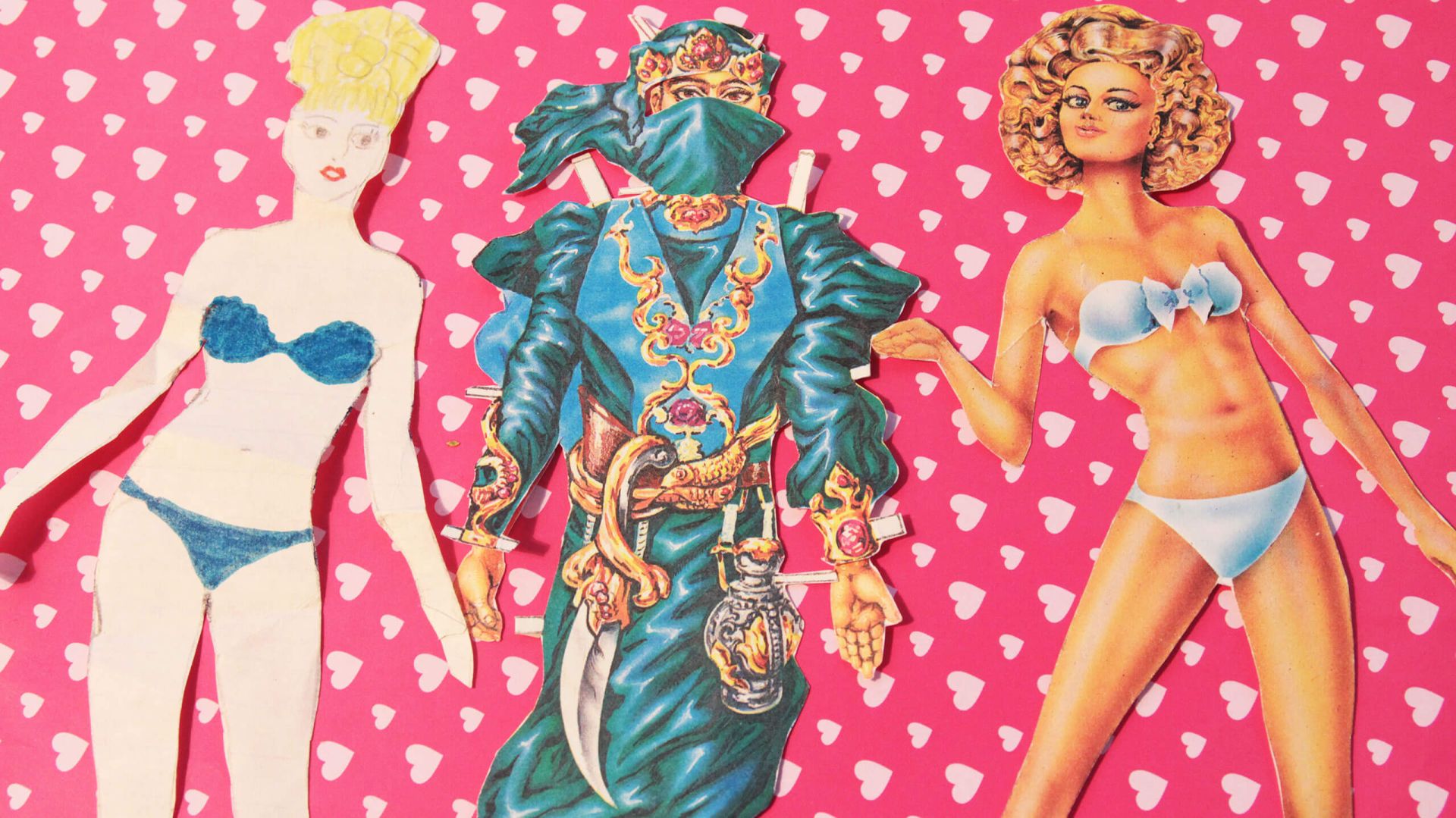

Toys hold a status as transitional objects, bearing essential significance in the developmental trajectory of children. Their role lies in aiding children in forging connections with the external world, enabling the differentiation between the inner and outer realms.

The concept of the transitional object was initially formulated by Donald Winnicott, who highlighted the unresolved nature of the challenge in perceiving reality. Winnicott proposed that it is through intense emotional experiences, such as those engendered by art, religion, and the realm of imagination, that individuals discover a means to alleviate the stress stemming from the coexistence of internal and external realities.

Within Tanya Akhmetgalieva’s series “Toys,” the notion of transitivity takes on a metaphorical essence. Firstly, the subjects depicted in these works often raise questions about the veracity of external reality. Secondly, Akhmetgalieva submerges us within the liminal realm that bridges the inner and outer dimensions. This is particularly evident as many of her works are intertwined with reminiscences and relics from her own childhood.

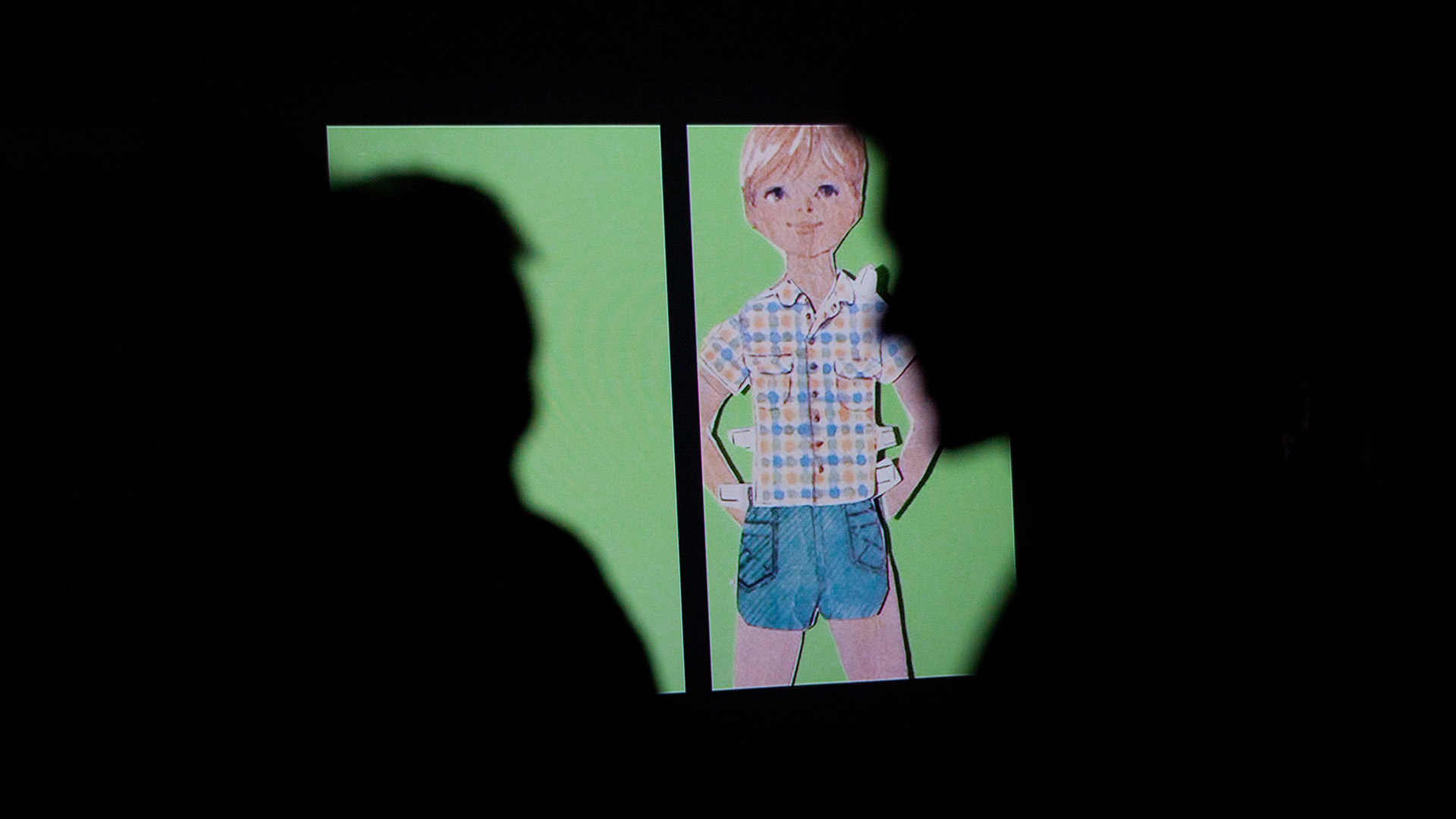

PAPER

2011, video 3 min 47 sec

Video & sound: Tanya Akhmetgalieva

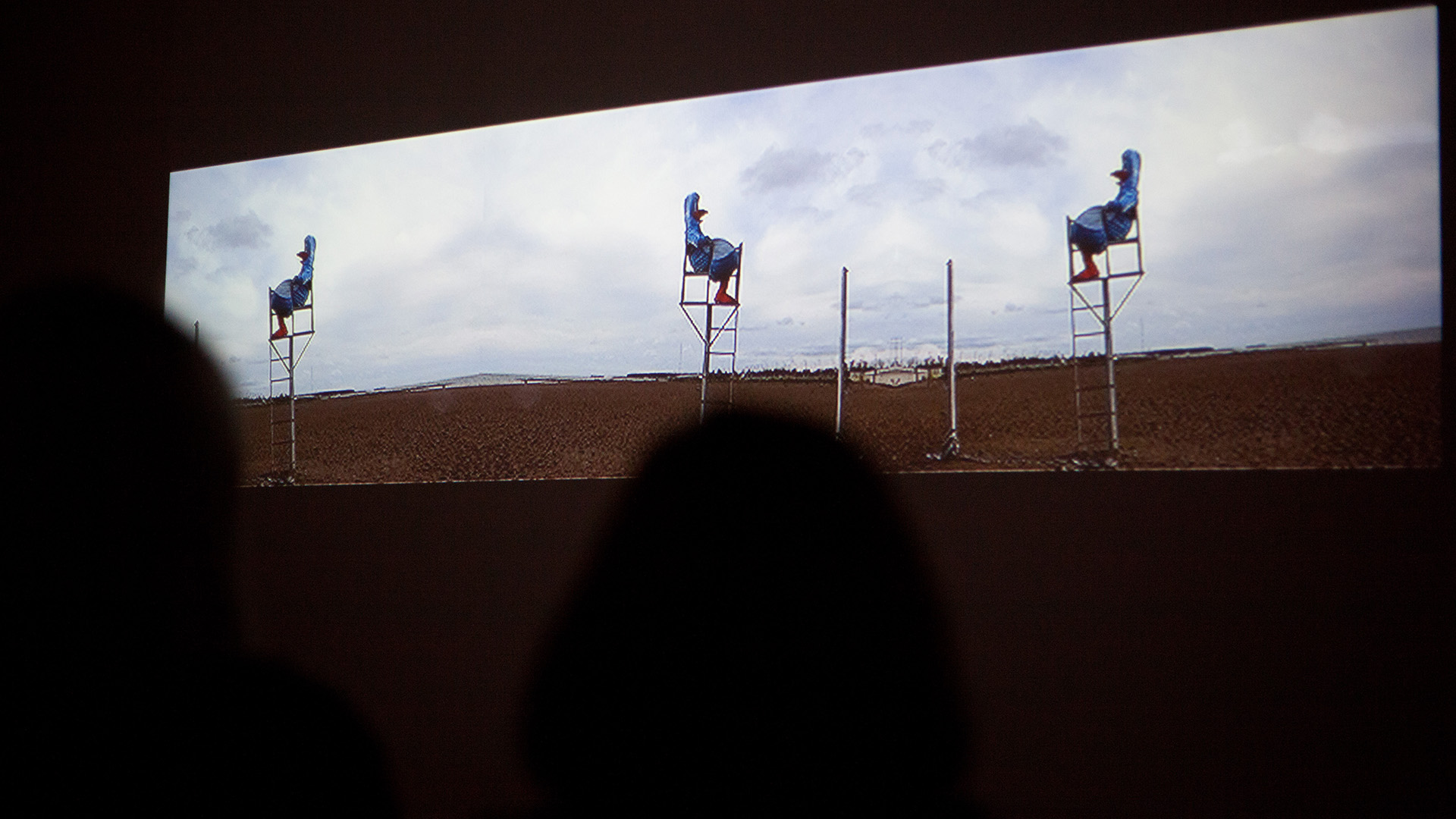

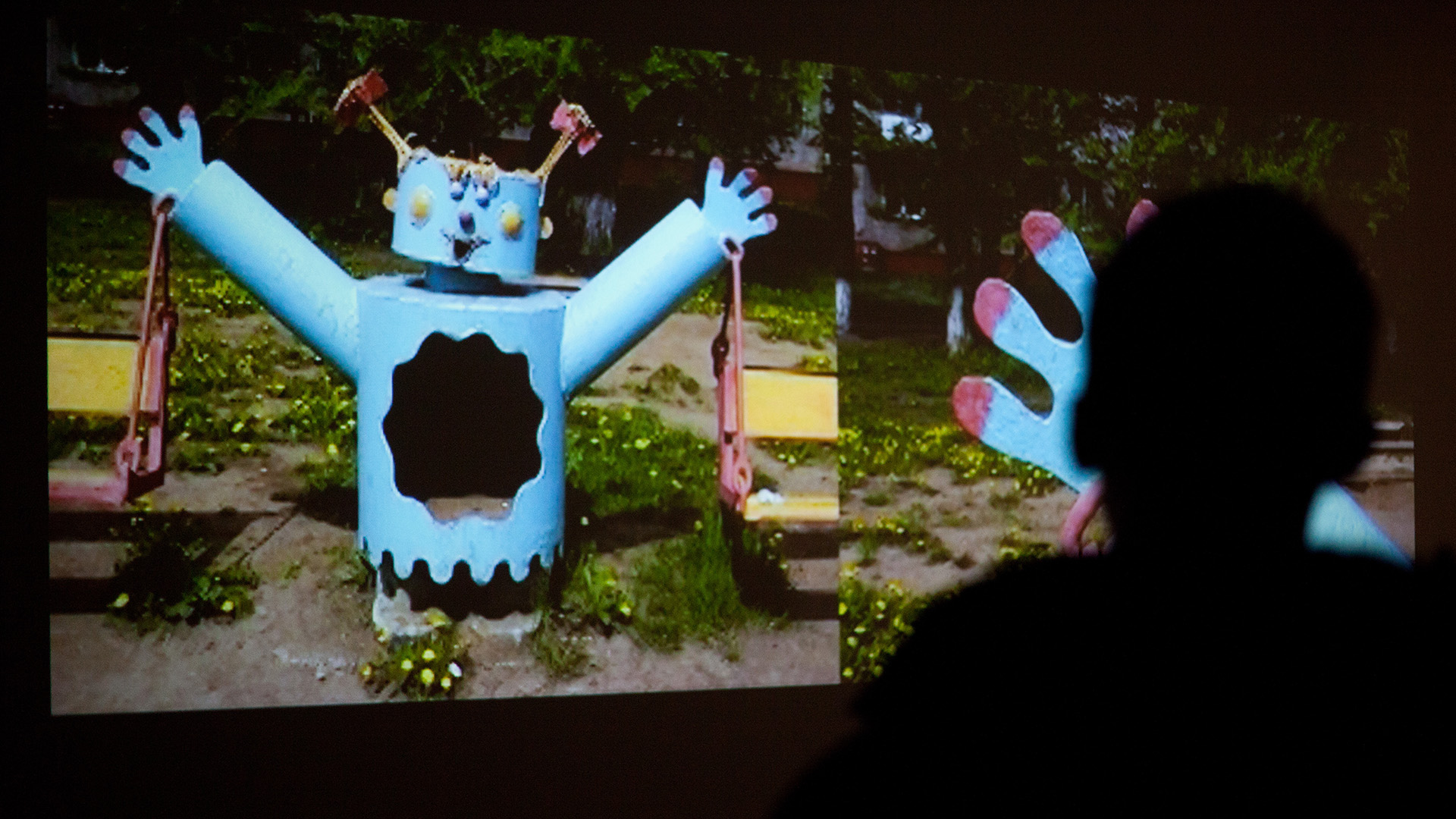

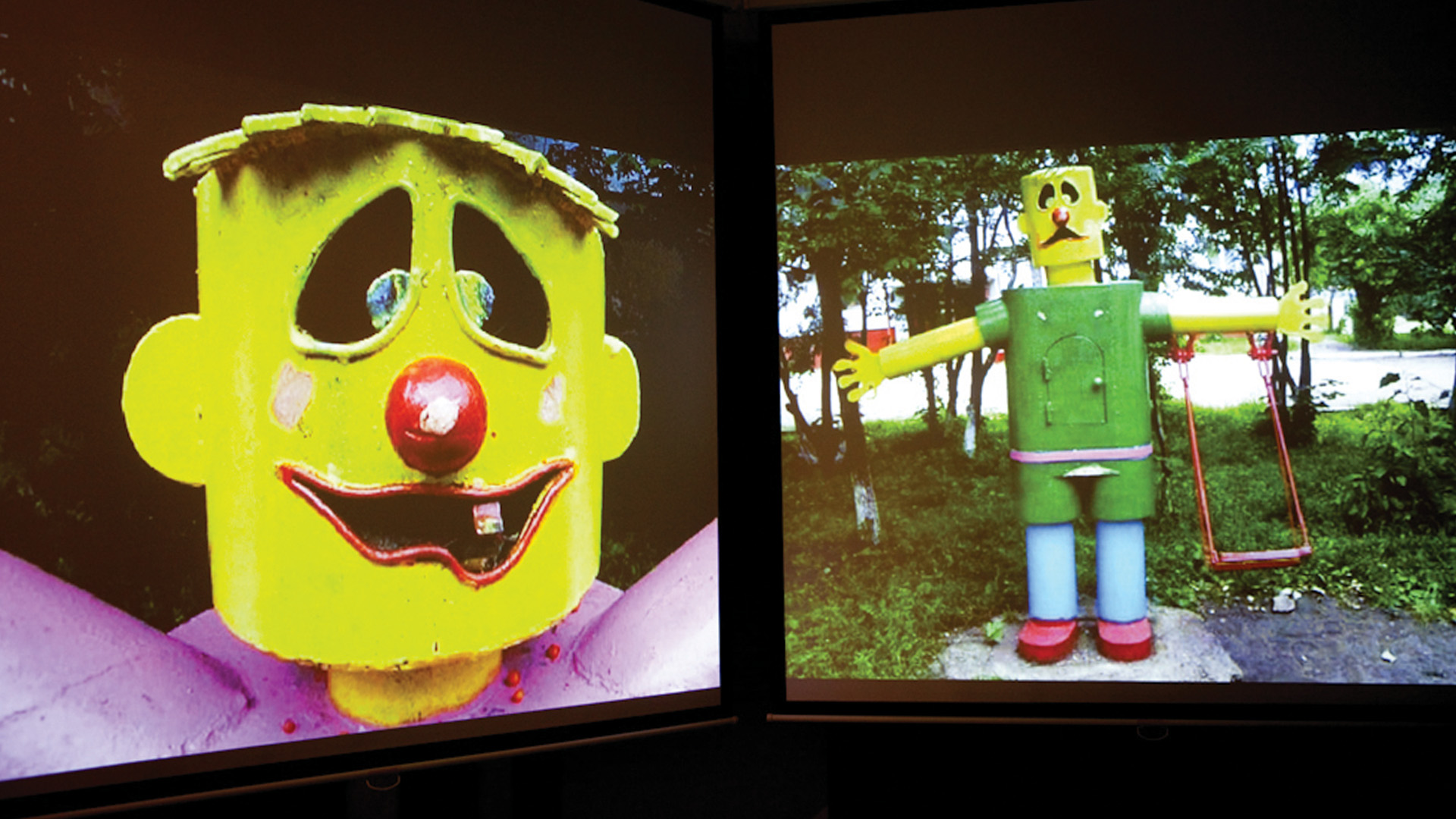

HAPPY CHILDHOOD, 2008

TWO-CHANNEL

VIDEO INSTALLATION, 03'50"

SOUND — IVAN VELLANSKY

Playgrounds were made by Anatoly Porotov in 1990-1995, Kemerovo, Russia

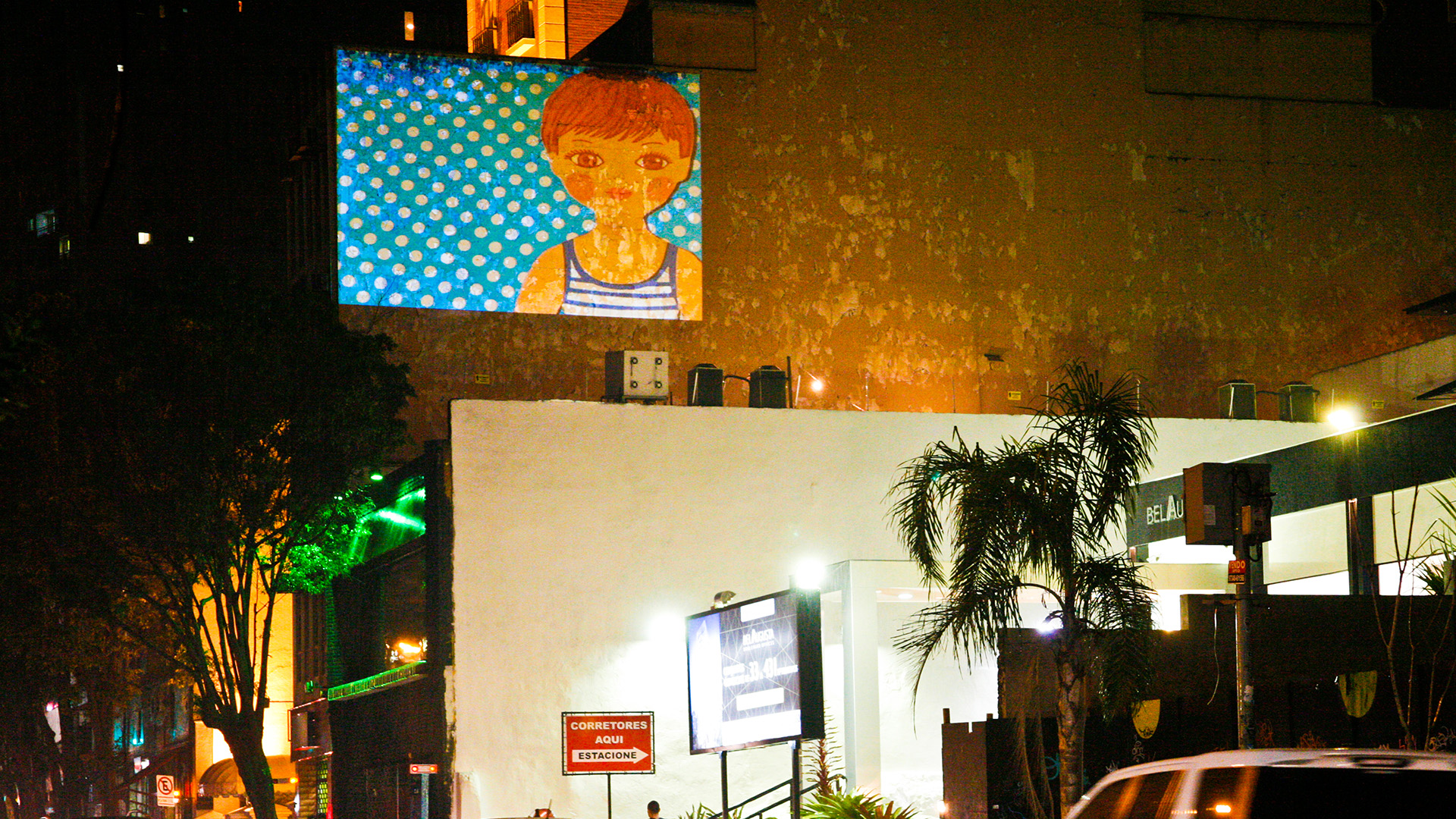

LITTLE CRADLE

2008, video installation

2 min 17 sec

Video & sound: Tanya Akhmetgalieva

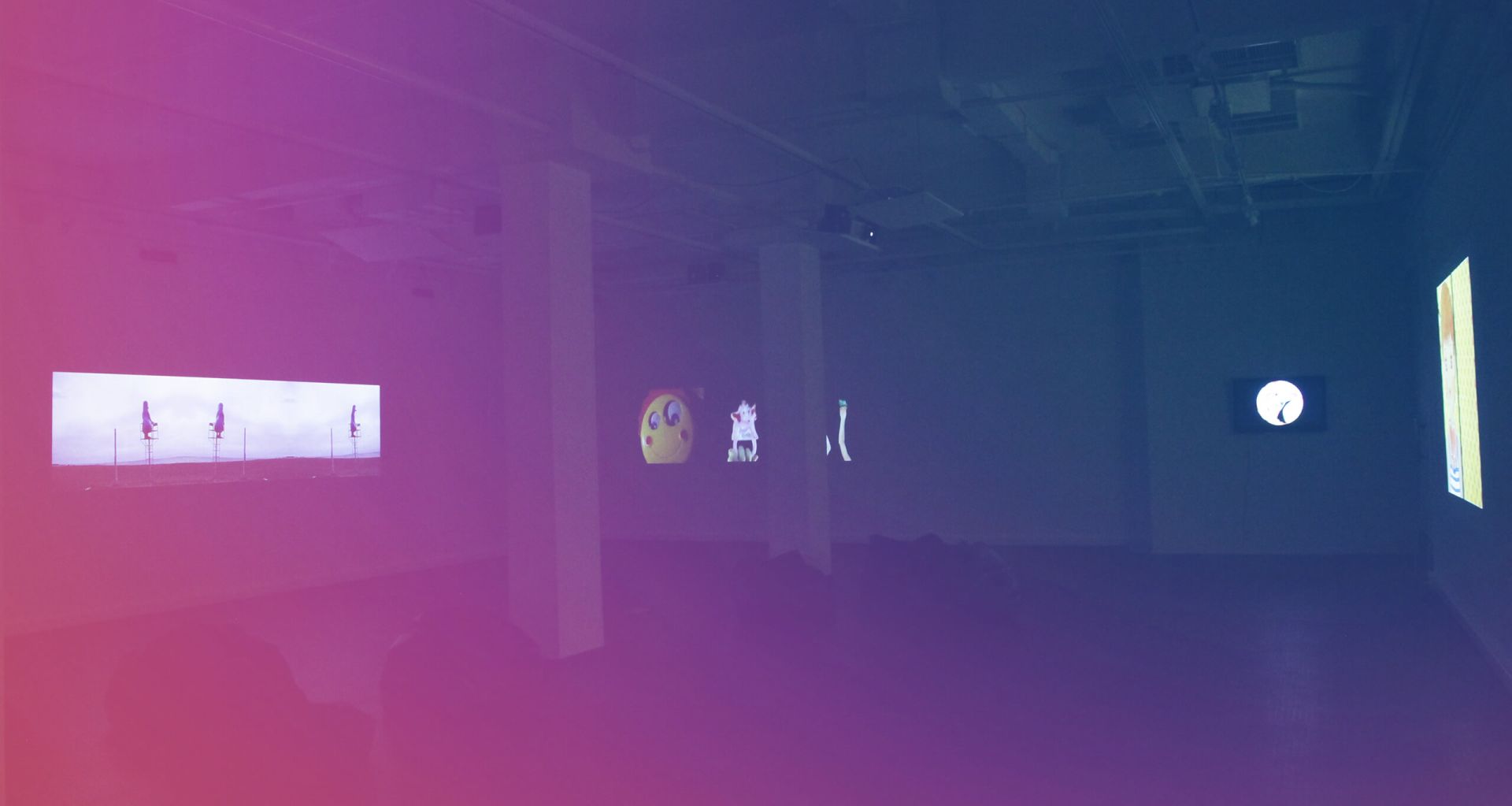

прощание vom arbeitsmarkt

2012, video installation

8 min 35 sec

Video & sound: Tanya Akhmetgalieva & Michi Muchina